The title to this post may seem like a strange question—I mean, of course iPads aren’t paper; they’re made of metal and glass and wiring, and not from wood pulp. iPads are the latest development in the evolution of computers, one of a string of developments that have revolutionized the way the world works in many fundamental ways over the past thirty or so years, while paper has remained fundamentally the same for many hundreds of years. So, is an iPad paper? No… but also, maybe, yes.

Last night a question was asked, and answered, that I think represents a major moment in the acceptance and use of technology in corporate and governmental environments. Many better writers than I am are discussing the events surrounding Wendy Davis’ filibuster on the floor of the Texas state senate, but I want to talk about an exchange that happened at slightly before nine o’clock last night when the question arose about whether Wendy Davis could read from her iPad during the course of her filibuster and it was determined that, yes, for the purposes of the current legislative process, an iPad counted as paper.

Senate parliamentarian just ruled that the word “paper” in the rules includes iPads. #txlege

— Elliot D. Williams (@elliot_dw) June 26, 2013

Although this wasn’t something that many people commented on, it caused a bit of a flutter amongst my iSchool friends. At the UT iSchool, one of our core courses included discussion of the infamous “Is an antelope a document?” article by Michael Buckland, which asks questions and encourages its readers to think in the broadest possible way about what constitutes a document.

@elliot_dw I feel like this is the legislative equivalent of our “is an antelope a document” article.

— Lydia Fletcher (@lamfletcher) June 26, 2013

In the iSchool, we’ve been trained and conditioned to question the fundamental building blocks of information, with the idea that we, as information professionals, are going to be involved at the most basic level with whatever changes in technology and legitimacy begins to arise in the world of documents and the media used to transmit information. The exchange between Lt. Gov. Dewhurst and Sen. Ellis was a teaching/learning moment for iSchoolers around the country.

@lamfletcher @elliot_dw Ellis did, in fact, use the term document in his question. They’re discussing it now.

— Anna (@nanners314) June 26, 2013

But what are the implications of this seemingly off-the-cuff exchange? What will the long-term effects be? Can iPads be considered paper in future governmental proceedings? Should they?

One of the things about iPads—and Kindles and Nooks and other tablets/eReaders—that people consistently point to in discussions about their benefits is their ability to store (or access) much larger quantities of books and documents than a single human person can carry around. If I printed out all of the PDFs, books, and other documents that I have loaded on my iPad (or stored in my Dropbox folders, which I can access via my iPad), I’d probably have far more material than I could carry around without a handtruck. I also feel like I’ve saved countless trees by using my iPad to read and annotate articles rather than printing them out and highlighting them like I did as an undergrad and during my first (pre-iPad era) master’s.

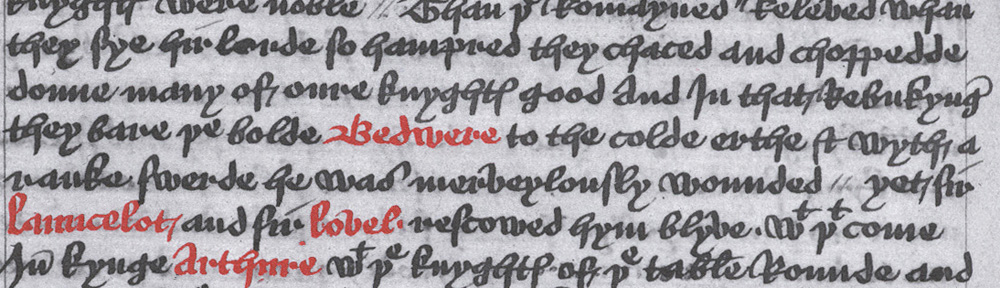

Sen. Wendy Davis of Fort Worth during her filibuster of SB 5. Austin, Texas (Photo: Chris Fox, 1080 KRLD)

The benefit to me of considering an iPad as paper in official governmental proceedings is that it can similarly reduce the environmental impact of printing and carrying so much paper. When Wendy Davis was filibustering yesterday, she had a binder full of the testimonies of women who had hoped to speak before the Texas state House of Representatives about the proposed legislation, as well as other relevant analyses and contextual information. Most senators had their copies of the relevant senate rulebooks and other documents that were relevant to the questions they asked Sen. Davis or the points of order or parliamentary inquiries that they raised over the course of the debate. That’s a lot of paper that could be saved, especially since things like the rules books are frequently revised and republished, and are likely to be revised in light of the rulings yesterday regarding giving aid to a senator during a filibuster and, yes, about whether an iPad constituted paper.

iPads are gaining ground as paper-equivalents in other areas, too: the U.S. Air Force and some major commercial airlines are beginning to replace the weighty bags of paper-based manuals and maps that pilots and other crew members carry with iPad apps designed for the purpose. Electronic flight bags stored on iPads are set to revolutionize air travel in a small but meaningful way: by removing the need to carry 35+ lbs of paper materials, it’s been estimated that “a minimum of 400,000 gallons and $1.2 million of fuel annually” can be saved, according to American Airlines, which is the first major national carrier to make the switch. Crucially to the topic at hand, the Electronic Flight Bags have been recognized by the FAA as being the equivalent of paper flight bags.

Of course, one of the major concerns that needs to be considered is about how secure iPads can be and whether they can compete with more traditional means when it comes to transporting important government documents. But doctors, bound by federal privacy laws, have been using iPads to access patient records for years, and storing information in paper form does not necessarily lessen the chance that it will be lost, stolen, or destroyed.

So, are iPads paper? Are antelopes documents? It’s a very exciting time to be an information professional and get to witness a sea change like this in how we regard information media.

I enjoyed reading your thoughts on my iPad (which of course you introduced me to!). I seem to use ‘this paper’ more often than any conventional paper these days…!

Very interesting post. Do you think the disjunction between iPad and paper book is sharper than between other text technologies (textnologies?), such as manuscript and print, scroll and codex, carved tablet and writing? Early typefaces tried to replicate handwriting, and a PDF article on my iPad looks identical to a printed version. It seems the shift in technology produces interesting questions like yours.

I was looking for a quote which happened during this debate – where the procedure’s president commented about how the document had been written in a different time and left room for appropriate interpretation (interesting thing to hear from a Texas republican, IMO!). Anyway, this was an interesting read. :) If you’ve any idea where I might be able to find a transcript, please let me know! :)

Pingback: The age of digital paper | Material Cultures of the Book Working Group

Pingback: Life After Library School, Chapter One | Book Archaeologist